“Burma Sahib”, by Paul Theroux, fictionalises George Orwell’s Burma years from 1922-27. Orwell’s novel “Burmese Days” does the same. How do they compare?

“Burmese Days” by George Orwell

Orwell’s Burmese Days, first published in 1934, is a fictionalised account of his time in the Indian Imperial Police in Burma (now Myanmar) from 1922-27. The writing is spare and elegant; the depiction of colonial Burma excoriating. Its grimness is exacerbated by breaking one of the key rules of modern writing, namely to ensure the main character is someone you “want to spend time with”.

The main character of Burmese Days is John Flory, a washed-up teak merchant who appears largely autobiographical. Flory, who lives in the imaginary town of Kyauktada in Upper Burma, is shallow, ineffective and befuddled by his sympathy to, as well as dislike of, the Burmese. He also loathes the British colonial expats amongst whom he finds himself, who, in turn, are racist and pompous.

The other main point of view is the corrupt Sub-divisional Magistrate of Kyauktada, U Po Kyin. U Po Kyin plots ceaselessly against the British, while also abusing all Burmese, and anyone else, with whom he comes into contact. He is a serial rapist, betrays insurgents who he encourages to rise up against the British, and schemes to destroy about the only sympathetic character in the book, the Indian doctor, Veraswami, a friend of Flory who tries with meagre resources to make life better for local Burmese.

“Burmese Days” – endemic racism

Burmese Days reflects the endemic racism of 1934. This is often hard to read, eg:

- Ma Kin, his [U Po Kyin’s] wife… was a thin woman of five and forty, with a kindly, pale brown, simian face.

- The butler, a dark stout Dravidian with liquid yellow-irised eyes like those of a dog, brought the brandy on a brass tray.

- The British Empire is simply a device for giving trade monopolies to the English – or rather to gangs of Jews and Scotchmen.

- Ma Hla May… [Flory’s Burmese mistress] had rather nice teeth, like the teeth of a kitten. He had bought her from her parents two years ago, for three hundred rupees.

Yet Orwell makes clear that the Burmese characters are more than a match for the Europeans:

- [U Po Kyin] was proud of his fatness, because he saw the accumulated flesh as the symbol of his greatness. He who had once been obscure and hungry was now fat, rich and feared. He was swollen with the bodies of his enemies; a thought from which he extracted something very near poetry.

- Ma Hla May… believed that lechery was a form of witchcraft, giving a woman magical powers over a man, until in the end she could weaken him to a half-idiotic slave.

“Burmese Days” – epigrams

Orwell is liberal with epigrams. I enjoyed the following:

- When one does get any credit in this life, it is usually for something that one has not done.

- Painting is the only art that can be practised without either talent or hard work.

- There is a short period in everyone’s life when his [sic] character is fixed for ever.

- Most people can be at ease in a foreign country only when they are disparaging the inhabitants. (I make a similar observation in my book Lessons in Diplomacy: “Eavesdrop on late-night chat in embassy bars or dinner parties from Austria to Zimbabwe and you will hear foreign nationals bemoaning the inefficiency, bureaucracy and inadequate work ethic of their hosts”.)

- There is a humility about genuine love that is rather horrible in some ways.

- It is a corrupting thing to live one’s real life in secret.

- All Englishmen are virtuous when they are dead.

“Burmese Days” – humour

There isn’t much humour in Burmese Days, but I liked this:

- Elizabeth was by nature a good listener. Mr Macgregor thought he had seldom met so intelligent a girl.

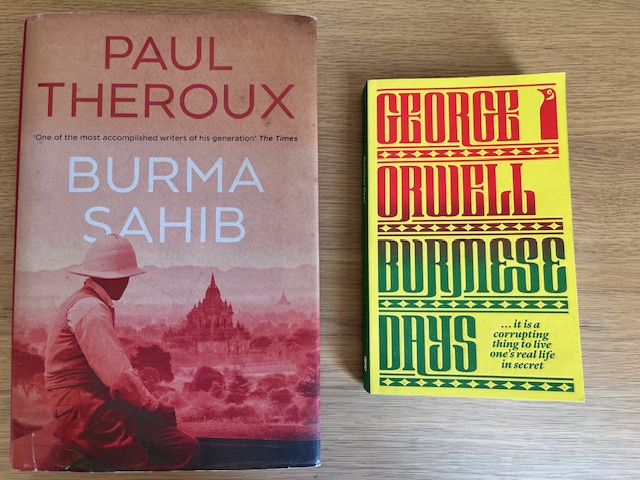

My copy of “Burma Sahib” was a birthday gift; of “Burmese Days”, borrowed.

“Burmese Days”: summary

All in all, Burmese Days is a vivid snapshot of 1920s Burma, from the point of view of a British colonial policeman – as George Orwell experienced it. It’s not a pretty picture, and it’s not (for me at least) an easy read. But it is intense and, if you can bear it, fascinating.

“Burma Sahib” by Paul Theroux

Theroux depicts the young Eric Blair – George Orwell’s real name – as both seduced and ashamed by empire. Just nineteen, a young police trainee straight out of Eton, he can’t stand up to older and more senior men and the institutions of empire. Result: he “drinks the Kool-Aid” of colonialism, even while hating both his colleagues and the empire itself.

“Burma Sahib” – racism

Boldly and, arguably, shockingly, Theroux ascribes to Blair (Orwell) plenty of racist sentiments. Blair keeps his relations the Limouzins, who live in the east of Burma, secret, because his Uncle Frank married “a local girl”. Meeting his cousin Kathleen, he cannot get his colleagues’ racist jibes out of his mind:

- It astonished him to think that this young woman was his cousin… and he could not rid himself of McPake saying “chee-chee” and “mongrel” and “They’re natural tarts.”

He is shocked when she identifies as a European:

- “Very sweltering is the weather in April and May. We suffer from prickly heat, not like the natives… I suffer torments each night. Very prevalent among we Europeans. For us, sunstroke ever menaces.” Blair hoped his dismay did not show on his face as she spoke, and she said the word Europeans in the chee-chee way, with the stress on the second syllable…

Blair is repulsed when he discovers that his Old Etonian friend Seeley plans to marry a “native”:

- Blair was moved by the tenderness in her eyes, envying Seeley for this veneraton, but still thought, a native.

Later, Blair watches events:

- And at this dinner here was Seeley, the owl of the Upper Fourth, and the black high court judge, pinching the deep-fried cakes in his fingers and exclaiming, “Toothsome,” referring to the curry as a “collation,” while his black daughter toyed with her rice mixture, flashing her eyes at Seeley… And Blair thought, as he had in Moulmein, What am I doing here with such people?

In another episode, Blair is jostled by a group of Burmese schoolboys in uniform (another incident borrowed from Burmese Days):

- “What are you monkeys laughing at?” he called out.

Other prejudice

Theroux depicts Blair (Orwell) as prejudiced in many other respects, too. When he learns his old school friend Hollis has converted to Catholicism, he says:

- “I once saw a crucifix – odd little souvenir. You tugged the top and out came a knife. I thought, what a perfect image of Roman Catholics.”

Later, he muses:

- As for Hollis the Catholic and Leila the convent girl – it was dire, the religion of criminal popes and poisoners, of vicious hypocrisy and fake piety, services conducted by snooty secretive priests in robes in a fug of incense. Bloody Catholics, worse than Jews, he wanted to say, but only smiled… saying he’d have to have an early night.

Hating the Empire

At the beginning of Burma Sahib, Theroux depicts Blair (Orwell) as more or less taking the British Empire for granted. But as his experience of Burma deepens, he becomes critical. Theroux suggests this is, in part at least, because Blair saw himself as a failure there:

- Blair hated the natives screaming at him, he hated the timber merchants for enslaving the elephants, he hated the police, he hated the empire – most of all he hated himself.

Theroux depicts Blair as resentful of his inability, within the colonial system, to live his life as he wishes. One example is church:

- After Eton he had vowed never to return to the cant and the sanctimony, the oppression of Christian authority. He’d vowed to keep his promise, to refuse to kneel, yet, as in so much else – Burma was a test of his beliefs – he’d failed, one of many self-betrayals. The empire was conscientiously Christian and uncompromising in religious matters. Law and life found their justification in the Bible, the king on all coinage was IND IMP – Emperor of India – and also FID DEF, Defender of the Faith. A simple silver one-rupee coin announced all the militancy of the Raj.

“Burma Sahib” – drinking songs

I am not sure if it is Theroux’s imagination or his research that has led him to include a handful of drinking songs, such as this one that Theroux ascribes to Blair himself:

Southern Railways do disparage//Consummation of a marriage//While the train is still at Waterloo,

Gentlemen reserve that function//While the train’s at Clapham Junction//When in fact there’s fuck all else to doooo!

I can find no trace of this gem on the internet, so can only infer that Theroux himself created it. If so, masterful.

Burma Sahib also features the war-time song “Bless ’em all“, which begins with the lyrics “They say there’s a troop ship, just leaving Bombay”, with a choice expletive replacing the “bless” in the chorus.

Banana wisdom

I liked the elegiac, somewhat surreal character in Burma Sahib of Robinson, an old soldier cashiered from the army for excessive fraternising with the Burmese. Blair (Orwell) admires Robinson for his iconoclastic tendencies and willingness to live outside the British community, who ostracise him. Robinson thus embodies Blair’s growing doubts about the empire. He also, arguably, shows the risks of resisting orthodoxy. Robinson later becomes an opium addict and a Buddhist, and blinds himself in a failed suicide bid.

Visited by Blair in hospital, Robinson condemns the empire as “a colossal bluff”. He then says that opium, while destroying him, helped him “to solve the timeless riddle of the universe”:

- “It came to me,” Robinson said, and he intoned in a low voice, “The banana is great but the skin is greater… Wisdom of the banana.”

“Burma Sahib”: summary

Burma Sahib is a great read: thoughtful, thought-provoking and entertaining. As a piece of research and imagination is is terrific. But it is perhaps in its depiction of how 1920s Burma formed Eric Blair/George Orwell, including his left-leaning and anti-imperialist views, that it is strongest.

“Burmese Days” and “Burma Sahib”: links

Not surprisingly, Burma Sahib seems to lift many details from Burmese Days. For example, John Flory’s dog is called Flo, as is Blair’s dog in Burma Sahib. Countless experiences attributed in Burmese Days to John Flory are incorporated in Burma Sahib as experienced by Blair, such as his encounter with a group of Burmese schoolboys (see above). In Burmese Days, John Flory’s Burmese mistress confronts him in the church when he is wooing Elizabeth, ruining his plans. In Burma Sahib Blair’s Burmese mistress confronts him in church when he is with his cousin Kathleen.

But Burma Sahib contains much that has no echo I could detect in Burmese Days. Blair’s British lover in Burma Sahib, Mrs Jellicoe, for example, has no visible parallel in Burmese Days. Nor could I detect a character similar to U Po Kyin in Burma Sahib.

Worth a read

Reading these two books one after the other was illuminating. I read Burma Sahib first, then Burmese Days. There are overlaps aplenty; but the different points of views mean there is next to no duplication. Best of all, reading both books gave me a stronger understanding of George Orwell (or Eric Blair) as a person. Theroux’s book, as he acknowledges, is fiction; and is deeply speculative. But it’s worth a look. If it encourages you to (re-)read Burmese Days – also fictional – that may be a bonus.

4 responses

Informative, illuminating. Thanks, Leigh. Must find B Days. I suppose we’re all victims of our times and background.

Glad you liked it! Always rewarding, to find a classic book that actually delivers something relevant, if in this case uncomfortable.

reading Burmah Sahib now and went looking for some terms (brit.slang) and came across this judicious review. I’ve been annoyed at author’s oblique use of the term ‘thakin,’ but I can only guess it means Master (?). It’s been tough going , but I must admit Theroux has showed me more about the English than I have found in any other authors, or have discovered on my own by traveling, so I remain a loyal reader.

Your site looks great, look forward to exploring it.

“cheers” and

regards

Chris Anderson

Washington DC

Hi Chris, thanks for this.

I agree that Theroux’s use of what are presumably Burmese terms that soaked into use by the English colonialists is often, somewhat unhelpfully, unexplained. The same thing happened on a vast scale in India proper where all kinds of terms were adopted permanently into English (think “veranda”) or came in, then have largely seeped out again (a cup of “char” for tea).

Hope you like the site! Part of the goal is to sell my own books, so do have a look at those.

Cheers (a previously obscure term that flourished in the ’80s and ’90s and is possibly now fading a bit)

LT